Education

Kind Reader,

I had but two years of formal schooling in my youth, and regretted mightily that I had opportunity for no more. And while it is a matter of some pride with me that I was able to rise above that early disadvantage, it might have been much otherwise.

Therefore do I find it disagreeable to think that any able and bright young man might be deprived of the chance of improving himself. Thus on September 13, 1749, I published a pamphlet urging my fellow Pennsylvanians to look to the future of both their children and their province by establishing an academy of learning in or near Philadelphia.

The academy came into being in 1751, a charity school was added in 1753, and at length the College of Philadelphia was chartered on June 16, 1755. A medical school was begun in 1765. Another college was chartered in 1779, but soon all are to be merged together under the title “The University of Pennsylvania,” the first university proper in America.

I wished the college to be devoted to the useful arts, that English learning be put before Latin and Greek, that the students be prepared with practical studies to enter the several professions and in other ways be rendered useful to the public.

It sorrows me that neither the rector engaged, the Reverend William Smith, nor the majority of the trustees, shared my vision of what the school should be, and gave preference to classical learning and even religious studies, which I did not desire. Times change, however, and I hope that in time the University may change as well.

In the meantime, in 1787, an academy for young ladies was opened in Philadelphia, and may soon receive a charter not unlike the university’s! ‘Tis a great shame that the education of women has been so long neglected, and perhaps this will offer some remedy.

As I have already written more than I intended here, I shall not give you all of my “Proposals” now, but save the rest for another day. I remain

your friend and servant,

B. Franklin

_______________________

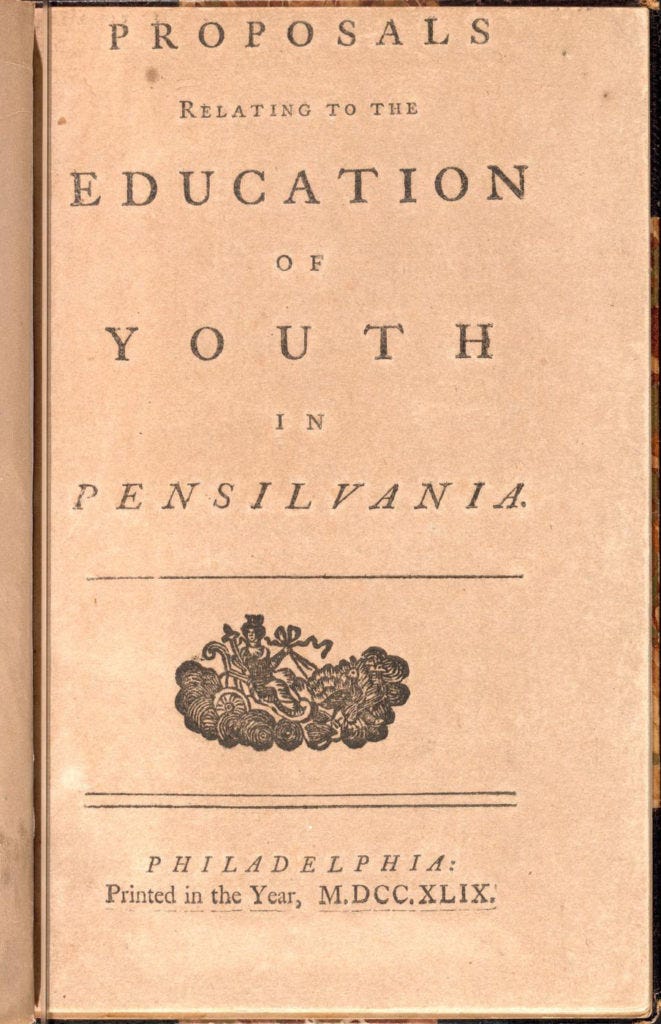

PROPOSALS RELATING TO

THE EDUCATION OF YOUTH IN PENNSYLVANIA

The good education of youth has been esteemed by wise men in all ages, as the surest foundation of the happiness both of private families and of commonwealth. Almost all governments have therefore made it a principal object of their attention, to establish and endow with proper revenues, such seminaries of learning, as might supply the succeeding age with men qualified to serve the public with honor to themselves, and to their country.

Many of the first settlers of these provinces, were men who had received a good education in Europe, and to their wisdom and good management we owe much of our present prosperity. But their hands were full, and they could not do all things. The present race are not thought to be generally of equal ability; for though the American youth are allowed not to want capacity, yet the best capacities require cultivation, it being truly with them, as with the best ground, which unless well tilled and sowed with profitable seed, produces only ranker weeds.

That we may obtain the advantages arising from an Increase of knowledge, and prevent as much as may be the mischievous consequences that would attend general ignorance among us, the following hints are offered towards forming a plan for the education of the youth of Pennsylvania.

It is proposed:

That some persons of leisure and public spirit, apply for a charter, by which they may be incorporated, with power to erect an academy for the education of youth, to govern the same, provide masters, make rules, receive donations, purchase lands, &c., and to add to their number, from time to time, such other persons as they shall judge suitable.

That the members of the corporation make it their pleasure, and in some degree their business, to visit the academy often, encourage and countenance the youth, countenance and assist the masters, and by all means in their power advance the usefulness and reputation of the design; that they look on the students as in some sort their children, treat them with familiarity and affection, and when they have behaved well, and gone through their studies, and are to enter the world, zealously unite, and make all the interest that can be made to establish them, whether in business, offices, marriages, or any other thing for their advantage, preferably to all other persons whatsoever even of equal merit.

And if men may, and frequently do, catch such a taste for cultivating flowers, for planting, grafting, inoculating, and the like, as to despise all other amusements for their sake, why may not we expect they should acquire a relish for that more useful culture of young minds? …

That a house be provided for the academy, if not in the town, not many miles from it; the situation high and dry, and if it may be, not far from a river, having a garden, orchard, meadow, and field or two.

That the house be furnished with a library, … with maps of all countries, globes, some mathematical instruments, an apparatus for experiments in natural philosophy, and for mechanics; prints of all kinds, prospects, buildings, machines, &c.

That the rector be a man of good understanding; good morals, diligent and patient, learned in the languages and sciences, and a correct, pure speaker and writer of the English tongue; to have such tutors under him as shall be necessary.

That the boarding scholars diet together, plainly, temperately, and frugally.

That to keep them in health, and to strengthen and render active their bodies, they be frequently exercised in running, leaping, wrestling, and swimming, &c.

That they have peculiar habits [uniforms] to distinguish them from other youth, if the academy be in or near the town; for this, among other reasons, that their behavior may be the better observed.

As to their studies, it would be well if they could be taught everything that is useful, and everything that is ornamental; but art is long, and their time is short. It is therefore proposed that they learn those things that are likely to be MOST useful and MOST ornamental, regard being had to the several professions for which they are intended.

All should be taught to write a fair hand, and swift, as that is useful to all. And with it may be learnt something of drawing, by imitation of prints, and some of the first principles of perspective.

Arithmetic, accounts, and some of the first principles of geometry and astronomy.

The English language might be taught by grammar; in which some of our best writers, as Tillotson, Addison, Pope, Algernon Sidney, Cato’s Letters, &c., should be classic. The styles principally to be cultivated, being the clear and the concise. Reading should also be taught, and pronouncing, properly, distinctly, emphatically; not with an even tone, which underdoes, nor a theatrical, which overdoes, nature.

To form their style, they should be put on writing letters to each other, making abstracts of what they read; or writing the same things in their own words; telling or writing stories lately read, in their own expressions. All to be revised and corrected by the tutor, who should give his reasons, explain the force and import of words, &c.

To form their pronunciation, they may be put on making declamations, repeating speeches, delivering orations, &c. The tutor assisting at the rehearsals, teaching, advising, correcting their accent, &c. …

_______________